From Asylum to Atrocity: Amelia Dyer’s Somerset Connection to One of Britain’s Darkest Crimes

By Laura Linham 27th Jun 2025

Amelia Dyer was one of Victorian England's darkest figures.

The murderer of countless infants placed in her care, she became known as the "Ogress of Reading" — a baby farmer whose crimes shook the nation. Yet beyond Reading and London, her story has a lesser-known chapter right here in Somerset, with connections to both Wells and Shepton Mallet.

Born in 1837 in Pyle Marsh, near Bristol, Dyer came from a modest family. The youngest of five siblings, she witnessed tragedy early when her mother was claimed by typhus, leaving the young girl to care for her until her death.

Those early encounters with illness shaped Dyer, later allowing her to mimic its signs to manipulate others.

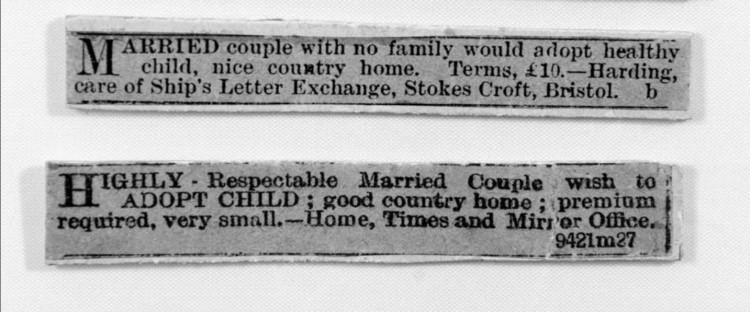

After working briefly as a corset maker, she trained as a nurse — a role that introduced her to the grim world of "baby farming". In Victorian England, unmarried mothers would pay a fee for someone to adopt and care for their child.

But for women like Dyer, this became an opportunity for cruelty. Instead of providing a safe home, she strangled infants with tape and disposed of their tiny bodies, often weighing them down and dropping them into the Thames.

In 1879, Dyer was first brought to court. Tried in Long Ashton, near Bristol, she was charged with failing to obtain the necessary licence for the maintenance of children — a serious offence at the time — and attempted suicide.

According to newspaper reports, the judge announced she would "reflect on her actions behind the walls of Shepton Mallet Gaol" for six months, serving hard labour. Though the court was close to the centre of Bristol, it fell within the jurisdiction of Somerset, making Shepton Mallet her place of imprisonment. She was acquitted of the charge of attempted suicide.

The prison experience marked the beginning of a long and brutal trajectory. Upon her release, Dyer returned to baby farming and soon graduated from neglect to calculated murder.

By the 1890s, suspicion was rising, and she responded by feigning insanity, gaining admission to the Somerset and Bath Lunatic Asylum just outside Wells. This stay was different from those she had manipulated before. "That was the worst of all," she said afterwards, and she never tried to use that tactic again.

By 1896, the authorities were closing in. Police traced the body of an infant named Helena Fry — weighed down with a brick — to an address linked to Dyer.

A raid on her home uncovered evidence of many more deaths: bundles of tiny clothing, letters from heartbroken mothers and pawnbrokers' tickets. There was also evidence she was planning to move to Somerset — possibly to restart her operation in Shepton Mallet, a rural area where she could have acted unseen.

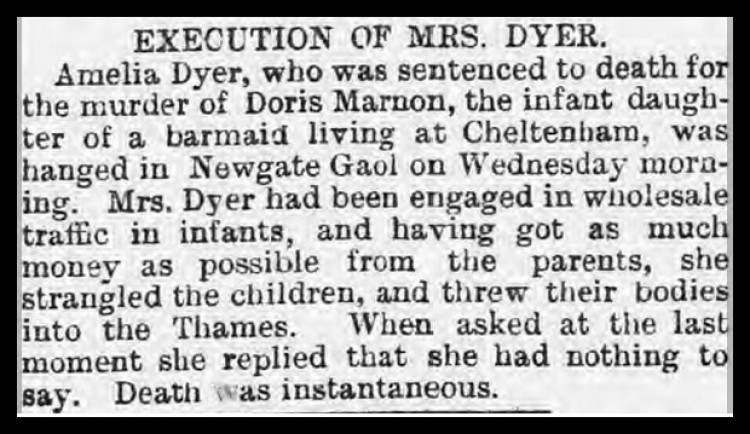

But her plan was thwarted. Tried at the Old Bailey for the murder of one of her victims, Doris Marmon, she was found guilty within five minutes. When asked if she had any final words, she replied simply, "I have nothing to say."

Yet throughout the proceedings, she offered a disturbing glimpse into her state of mind. "You'll know mine by the tape around the neck," she said to police.

Amelia Dyer was hanged at Newgate Prison on 10 June 1896. In the three weeks before her death, she filled five exercise books with a "last and only confession". When a chaplain asked if she had any further statement, she handed them over, saying: "Isn't this enough?"

Although most of her crimes were committed in Reading and London, Somerset played a pivotal role in Dyer's story.

Her time at Shepton Mallet marked the first point where the law truly caught up with her, and the Wells asylum was a rare place where she felt confined herself. Without this link to Somerset, one of Britain's most prolific murderers might have evaded capture for longer.

Today, Amelia Dyer's brutal legacy reminds us how cruelty can hide in plain sight — and how even the quietest corners can bear witness to the darkest chapters of history.

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

glastonbury vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: glastonbury jobs

Share: