How the Black Death changed life forever in Somerset’s market towns

By Laura Linham 22nd Jun 2025

When the plague swept through Glastonbury, Wells, Shepton Mallet, Frome and Street, it didn't just kill – it reshaped everything

It started with a cough.

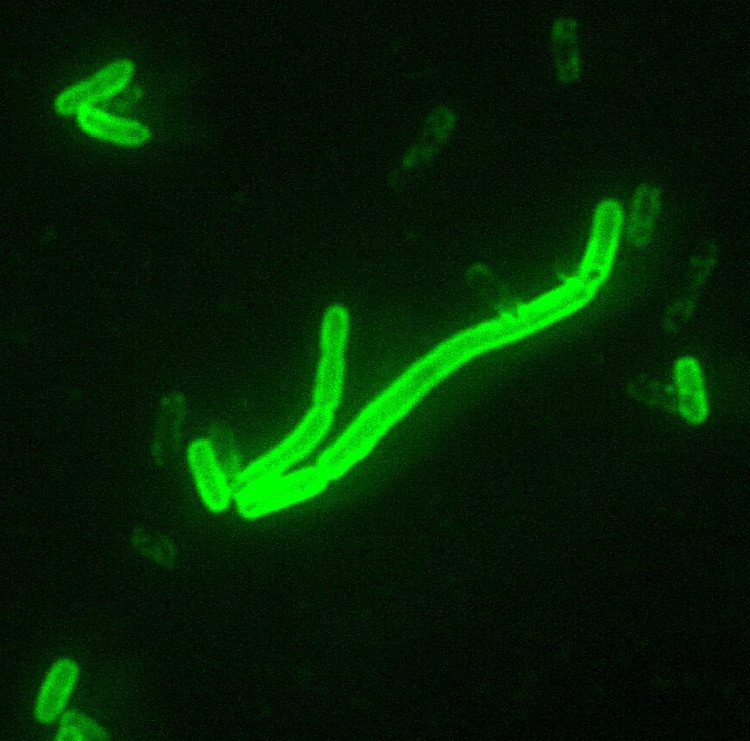

Somewhere in Central Asia in the early 1340s, a deadly bacterium – Yersinia pestis – began creeping west along the Silk Road. Carried by fleas on black rats, it made its way onto merchant ships and into the cities of Europe, killing fast and without mercy. By 1347, it had reached Sicily. By June 1348, it had arrived in Dorset. Within weeks, the Black Death was moving across the South West, faster than anyone could comprehend.

By the end of that year, Somerset was in its grip.

A death like no other

This wasn't a slow decline. Victims often developed sudden fever – up to 41°C – alongside vomiting, nausea, joint pain, and crushing fatigue. But what terrified people most were the buboes – large, painful swellings in the groin, armpits or neck, filled with pus and blood. In the words of 14th-century writer Boccaccio:

"It first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours... some as large as a common apple, others as an egg... black spots or livid marks appeared... such also were these spots on whomsoever they showed themselves."

Most died within two to seven days. Without treatment – and in 1348 there was none – 80 per cent of those infected did not survive.

The fear spread as fast as the disease. And in places like Wells, Frome, and Shepton Mallet, the toll was catastrophic.

Contemporary records suggest up to 50% of the population in many areas of Somerset died between autumn 1348 and spring 1349.

Parish records and diocesan registers support these figures. In Wells, where ecclesiastical records are particularly detailed, 47% of the clergy died – an indirect but compelling indicator that the lay population was similarly affected.

In Shepton Mallet, local tradition and later chroniclers claimed that just 300 people survived the first wave. Estimates suggest the pre-plague population may have been around 600–800, meaning the town lost well over half its inhabitants – possibly closer to 70%.

In Frome, a manorial inquest in April 1349 noted that "many dwellings... were standing empty because most of the tenants were dead". Across Frome's manors, nearly every recorded tenant had either died or vanished. Contemporary data suggests a 40–60% population loss.

The village of Holcombe, just north of Shepton Mallet, was so devastated by the Black Death that the original settlement – located around the church – was abandoned. Survivors relocated the village a mile away, where it still stands today. The mounds of earth around the church are believed to cover the buried remains of the plague-ravaged homes.

Local legend even links the tragedy in Holcombe to the nursery rhyme Ring a Ring o' Roses.

Street and Glastonbury: spared – but not untouched

Not everywhere was equally affected.

In Street, remarkably, no clergy deaths were recorded during the 1348–49 outbreak – an anomaly in the diocesan records. This has led historians to suggest the area was partially spared, possibly due to its relative isolation and the natural barriers of the moors and Polden Hills. The actual population loss is unknown, but believed to be significantly lower than the county average.

Glastonbury, too, seems to have avoided the worst of the initial wave. The Abbey's own records mention losses, but not collapse. The monastic community survived, and the Abbey went on to absorb lands and tenancies from neighbouring depopulated villages in the decades that followed.

That said, the surrounding parishes weren't as lucky. Many rural vicars died, and isolated settlements disappeared altogether.

Geoffrey le Baker, an Oxford clerk, wrote about the description of the spread throughout England:

"At first it carried off almost all the inhabitants of the seaports in Dorset, and then those living inland. From there it raged so dreadfully through Dorset and Somerset, as far as Bristol. The men of Gloucester refused to allow people from Bristol into their region, as they all thought that the breath of those who lived amongst people who died of plague was infectious.

At last it attacked Gloucester, Oxford and London, and finally the whole of England so violently that scarce one in ten of either sex was left alive.

As the graveyards did not suffice, fields were chosen for the burial of the dead. A countless number of common people and a host of monks and nuns and clerics as well, known to God alone, passed away.

It was the young and strong that the plague chiefly attacked. This great pestilence, raged for a whole year in England so terribly, that it cleared many country villages entirely of every human being."

Wells: a city overwhelmed

Wells bore the full weight of the first wave.

In January 1349, Bishop Ralph of Shrewsbury issued an extraordinary order: laypeople could hear each other's confessions, including women. The decision was prompted by the collapse of the clergy – nearly half of all parish priests in the diocese had died within weeks.

Church bells tolled day and night. Services were halted. In nearby Yeovil, a thanksgiving service turned into a riot, with residents trapping the bishop inside a church overnight – furious that the Church had failed to protect them. Similar sentiments likely simmered in Wells, Shepton, and Glastonbury.

Out of the chaos, new institutions emerged. The famous Vicars' Close – still standing today – was only built because the death of a canon freed up the land. It offered secure housing for the remaining clergy, and signalled a rebuilding of the spiritual heart of the city.

Economic collapse and uneasy recovery

The Black Death didn't just empty streets and churches – it brought the local economy to its knees.

With entire households gone, markets in Frome, Shepton Mallet and Wells came to a standstill. Fields were left unploughed. Trade halted. Manorial and abbey records show vast numbers of vacant tenancies. In some areas, agricultural output simply ceased. The Carthusian monastery at Hinton Charterhouse later petitioned the King for permission to bring in outside labourers, reporting that almost all their servants and retainers had died, and their lands lay "waste and uncultivated".

Yet out of this devastation came lasting change.

With labour suddenly scarce, surviving workers were in demand – and they knew it. Wages rose. Peasants began to push back against old feudal obligations. In village after village across Somerset, villeins became tenants, and tenants became freeholders. Power began to shift.

Many landowners, no longer able to sustain labour-heavy farming, began converting arable land to pasture for sheep. This required fewer hands and yielded higher profits – especially as wool prices soared. Over the next decades, the countryside adapted.

By the late 14th century, Shepton Mallet and Frome were emerging as textile towns. Flemish and French weavers – fleeing conflict on the continent – settled in Somerset, bringing new skills and helping to lay the foundations of a thriving cloth industry.

In Shepton, the textile trade would become central to its identity. What had begun as a survival strategy after plague would grow into an industry that shaped the town for generations. The same was true in Frome – both towns rebuilding not as they were, but as something new.

A second wave

Centuries later, the Black Death still haunted Somerset.

In 1626, as the plague returned, Canon Timothy Revett scrawled two Latin words in the Cathedral expense ledger: grassante peste – "the plague is raging".

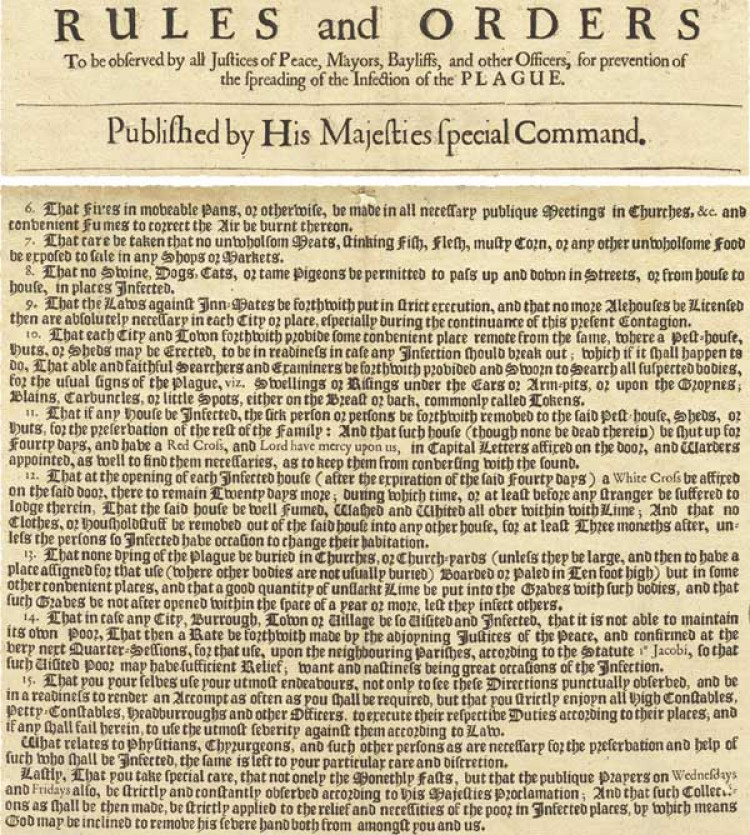

That same year, records show only two canons were still present in Wells – Revett and Richard Adams – both dangerously ill. Parish registers show burials surged again from October 1626 to summer 1627. In St Cuthbert's, three members of the Plumley family died within weeks. City fairs were cancelled, houses locked down, and travel tightly restricted.

Revett survived. But the image of him, perhaps already feverish, pausing to write those two urgent words in a different ink, has endured as a stark reminder of how raw the memory of plague remained.

The aftermath

The Black Death didn't just kill. It broke the world, and forced the survivors to rebuild.

In Street, Glastonbury, Shepton Mallet, Frome and Wells that meant rethinking how towns were organised, how labour worked, and who had power. It meant new trades, new settlements, and sometimes, new locations altogether.

Some communities never came back. Others re-emerged stronger – but changed.

Even the architecture shifted. With skilled masons gone, the detailed stonework of the Decorated Gothic style gave way to the simpler, more uniform Perpendicular style – a visible legacy of the plague's toll.

And folklore remembered what history feared to write. In Somerset, stories of a winged wyvern spreading death across the hills became part of the landscape's identity. In Holcombe, the rhyme Ring a Ring o' Roses was said to echo the deaths that drove the village from its original home.

A changed Somerset

Social structures shifted. Faith was tested. Entire generations vanished.

And yet, life went on.

What emerged was different – more resilient, more open, and forever marked by the trauma of that terrible winter.

Street, Glastonbury, Shepton Mallet, Frome and Wells all survived.

But they were never quite the same again.

CHECK OUT OUR Jobs Section HERE!

glastonbury vacancies updated hourly!

Click here to see more: glastonbury jobs

Share: